West Ham United fan and football nostalgist Sid Lambert looks back at a player who starred for the Hammers in the early 90s...

I sometimes wonder what they made of Christmas 1989 in the Quinn household. Big Jimmy had just completed a £320,000 move – the biggest transfer fee of his career – to sign for West Ham United, the biggest club of his career to date. It should have been a cause for great celebration.

He could have been forgiven for enjoying an extra mince pie and mulled wine in front of the Only Fools And Horses festive special. This was the start of a brand-new adventure – one that could finally lead the big Irishman to top-fight football. Play his cards right and this time next year he could be a millionaire. Au contraire, Rodders, au contraire.

Unfortunately for Jimmy, the Club he had joined was enjoying the same sort of success Derek Trotter had with his new range of underwater candles.

‘WE WERE RUBBISH’

The Great Reset under Lou Macari had flattered to deceive. The Scot – who faced the unenviable task of replacing the legendary John Lyall following relegation – had chopped and changed with personnel, fiddled with formations and tweaked the team in search of consistent promotion form. The more patient observers had said that Macari’s team were struggling to find their identity. Well in December, we found it. We were rubbish.

Games against Stoke, Bradford, Oldham, Ipswich and Leicester yielded the sum total of one point and one goal in a month that ranks amongst the very worst in the Club’s history. We were mid-table in the second tier. Our squad of supposed title contenders were a soft touch in a division where you had to scrap for three points every single week.

Even our cup form, which had at least given the season some hope, deserted us. We lost 4-3 to Chelsea in the Zenith Data Systems Cup, a tournament brought in after English clubs were banned from European competition in light of the Heysel Stadium disaster in 1985.

So, in December, Macari rolled the dice again and brought in three new faces to shuffle the pack. Mark Ward was off to Manchester City in exchange for Trevor Morley and Ian Bishop. And arriving alongside them was the towering figure of James Martin Quinn, or ‘Jimmy’ as he was known up and down the Football League.

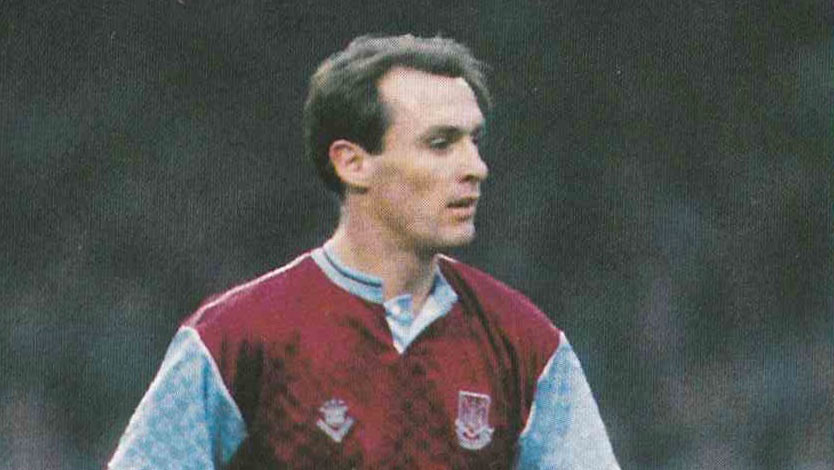

We got our first sight of the new arrival in a much-needed win over Barnsley on New Year’s Day 1990 that propelled us to tenth in the table. Whilst Morley stole the show with two goals, it was his strike partner that commanded the gaze of curious onlookers. There was something unusual about our new centre-forward.

At first, you couldn’t quite put your finger on what it was precisely that made him such an oddity. It wasn’t his sheer size. Yes, he was tall, and he was imposing. But then again, so was Big Ben.

And then – an epiphany. You see, much like the country’s most iconic clockface, Jimmy Quinn didn’t move.

HEADING UPWARDS

Humanity has tolerated many legends over the years: Bigfoot, the Bermuda Triangle, the Loch Ness Monster. But no football fan has ever produced photographic evidence of Jimmy Quinn breaking into a jog. That would be preposterous. And the most extraordinary thing was that he didn’t need to. The Northern Ireland international had completely broken football’s algorithm. He had become a seasoned goalscorer simply by standing still.

He notched his first for the Club in a gritty 1-1 draw at Plymouth during the dying embers of Macari’s reign. But it was under new boss Billy Bonds that Quinn really caught fire. He added a completely new dimension to our forward line. For so long, we’d lived on our reputation as the Academy of Football. But this league was like trenched warfare. And you needed some aerial artillery. With Quinn in the side, we could get it launched.

His forehead became one of our most deadly weapons. He scored 12 goals in 19 games as we made a late run for the Play-offs. The goals were all eerily similar: a cross to the near or the far post and the Big Man would be there, perfectly positioned, to nip ahead of the defender and nod it into the net. There were occasional moments of finesse with his feet – Quinn had a good touch and could link play nicely – but we all knew his role in the side. Most weeks, his boots were cleaner than Mother Theresa’s driving licence.

His lack of movement earned him the moniker ‘Jimmy the Tree’ from the terraces, a nickname rooted in affection for a player who was becoming very popular in these parts of London. He started the following season on the subs' bench behind Morley and Frank McAvennie, until a diving header (of course) against Ipswich restored him to first-team duty.

IMPACT

From then on, he was a key part of the side that pushed Oldham all the way for the title. Whether he was in the first XI, or summoned from the bench, he always made an impact. When promotion was sealed, Quinn had a very respectable record of 22 goals from 57 appearances. And after years of doing the business in the lower leagues, he’d finally earned his shot at the top table of English football.

So, it came as a huge surprise when the striker was sold to Bournemouth over the summer for the relatively paltry fee of £40,000. He was still a regular for his country and even if he was an unlikely starter in the top-flight, surely his frame alone would make him a useful option from the sidelines. To this day, I still believe he would have contributed just as much as the likes of Mike Small, Morley and McAvennie in a season when we tumbled out of the top tier at the first attempt.

Instead, he went to Dean Court and set about doing what he did best: scoring goals. He notched 19 in 43 games before moving to Reading (where he briefly teamed up with Morley again) and making himself a cult hero well into his late thirties.

It’s now over 30 years since Quinn lined up in Claret & Blue, but for fans of a certain vintage ‘Jimmy the Tree’ still holds a place in our hearts.

*Sid Lambert's latest book Highs, Lows and Di Canios: The Fans’ Guide to West Ham United in the 90s is out now. Visit www.conkereditions.co.uk to revisit the rollercoaster ride of one of the most turbulent decades in Claret & Blue history.