When West Ham United welcome Chelsea to London Stadium on Saturday, both teams will once again stand in unison with a clear message that there is No Room For Racism in football, or life in general.

Since launching in March 2019, the No Room For Racism campaign has brought together the Premier League’s wide-ranging work promoting equality and inclusion across all areas of football.

For Ade Coker, the work being done to endorse equality and challenge racist behaviour across football is something to applaud.

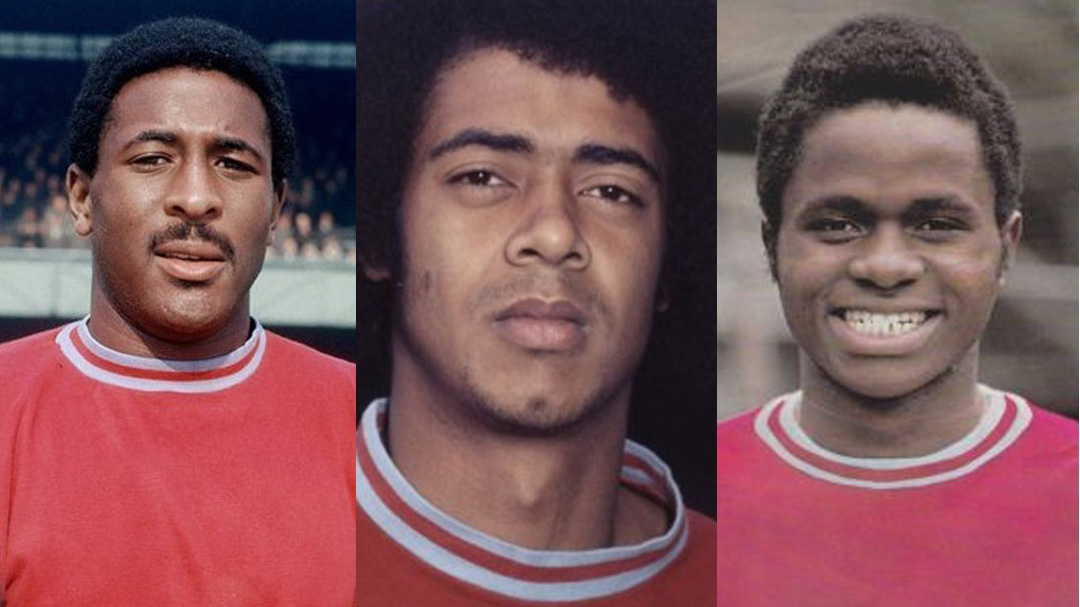

The Nigerian-born forward made his West Ham United debut in 1971, scoring in a 2-0 win over Crystal Palace. Just a few months later, the then 17-year-old etched his name in history as he, Clyde Best and Clive Charles took to the pitch in Claret and Blue together against Tottenham Hotspur. That April afternoon in 1972 marked the first time three Black players appeared in the same Football League team.

Growing up in London in the 1970s presented concerning challenges for young, Black men like Coker. Abhorrent, racist language and threatening behaviour were unfortunately the norm for the young attacker and his Black teammates.

Half-a-century on, Coker remains resolute that the issue of racism will be eventually eradicated. Not just from football, but from society.

Campaigns like the No Room For Racism initiative are crucial to that objective.

“Things can still be better,” Coker confirmed. “From what it was, to what it is now though, I’m so glad that the media looks to bring awareness around racism to the public. The media is showing people what racism is about, and it’s up to us as people to learn and decide whether to be a part of the problem or part of the solution.

“Racism back then, to what it is now…back then, people would say it to your face. Nowadays, racists hide behind their phones and computers and Tweet out certain things about other people. The only thing I can call those people is ‘cowards’.

“Change is coming. It will happen. It may not completely happen in my lifetime, but it will happen because the wider community are being made aware of the problems. People are being exposed to it, and the people who are saying racist things and committing racist acts are being exposed as well.

“Organisations like the Premier League and people like Manchester United’s Marcus Rashford are leading that campaign of awareness, to make things better. He, and others like him, are to be commended.

“The problem will always be there, but problems are there to be solved, and when you’re part of the solution it gives you power over the problem. There will always be power over the racism problem.”

Threats of violence and unacceptable, racist terms were levied at Coker and his Black teammates Best and Charles with inexcusable regularity during the early 1970s.

One particular threat still remains with Coker to this day.

“Those were hard times,” he reflected. “It wasn’t easy. There were racial slurs, racist names, and there wasn’t the concept of ‘racism’ back then.

“It was so bad at one point that even the fans actually threatened to throw acid in our faces. That was a very hard one. Clyde handled it better than I could, but Ron Greenwood told us he was going to sit us out for a couple of games, because they couldn’t protect us.

“Besty, more than anybody, took the brunt of the whole thing. Clive and I came after him, even though we still got our share of it, and we learned from Clyde in terms of how to behave and handle it.

“Was I scared? Oh yes, I was scared. You look at the way the grounds were and it was hard to protect anyone. You could imagine something like acid being thrown at you actually happening. It was a real threat so yes, I was scared. I was glad, to an extent, that Ron took me out for a couple of games.”

As much as racist behaviour followed Coker, the forward still credits West Ham United for never seeing him – or any player – just for the colour of their skin.

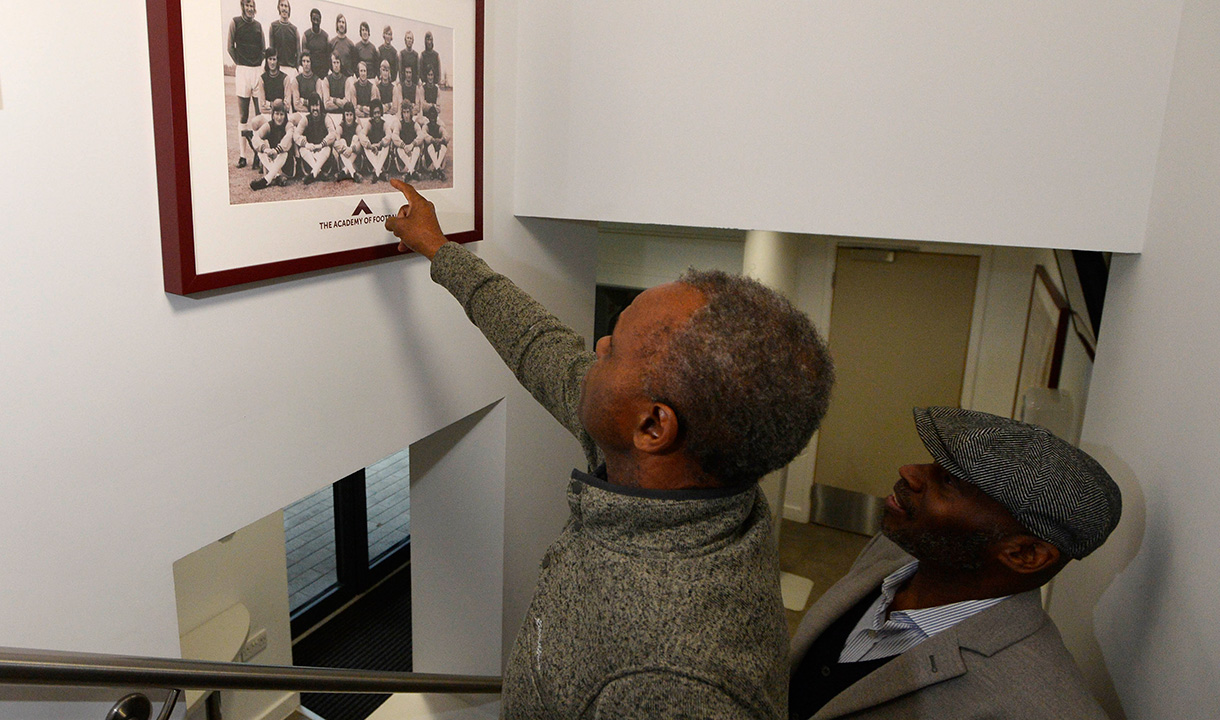

It was an attitude not shared by every club in the Football League, which made Coker’s time learning under the guidance of the management team at Chadwell Heath even more special.

He added: “Ron Greenwood, John Lyall and Bill Lansdowne, what they did for players and for the game will go down in history forever, in my opinion.

“They, at the time, did not see a player’s colour. They saw his talent and they developed his talent. They developed that person as a player and a human being, and gave him a chance on the pitch. They saw the person, not the colour.

“I won’t name which one, but I went to a team for a trial before I came to West Ham and I was even called names by people there. I never went back because of that. I came to West Ham a few days later and it was just coming home. I knew this was where I wanted to be.”